Back in June, I began reading the book What If Everybody Understood Child Development? by Rae Pica. I'm grateful for Rae and the thinking she has inspired on these issues in education. (You can see all the posts in this blog series on the Book Study page.)

All of the issues that Rae has raised are important for young kids and their teachers. In fact, as I read the book, I also kept seeing blog posts and news stories that connected with it. The post that continues to resonate with me is Amanda Morgan's post "Allowing Children to Bloom in Season" (Not Just Cute).

She compares the growth and development of children to flowers in a garden. There's a predictable pattern to the growth and development. But each flower (and child) blooms at its own time. And for children sometimes that blooming season lasts longer or comes later.

As I pondered what I had read in Rae's book (and saw repeated in other places), I thought about the people that are proposing some of these challenging practices. I really think that teachers and most administrators have the same goal in mind--children who grow and learn and are successful. But sometimes in trying to get there, adults forget who kids are and how they are. They try "short cuts" to success and end up doing things that are not the best for them. They don't think about development. Or they are trying to be more expedient and don't realize the consequences of those choices.

As I blogged earlier, I think we teachers should think about the kids first. Then we can make intentional and balanced choices. Overall, that's my takeaway from this book. Think about the kids. Make intentional choices that relate to helping kids bloom in their own seasons. And take a balanced approach to technology, educational trends, and so forth.

The key quote from this book, the one that comes back to my mind again and again: "We talk so much about preparing kids for school but give very little thought to preparing schools for kids." (Rae Pica)

As I create learning environments for kids, I want to think about them and how I can prepare that environment for them--prepare the environment according to child development and according to the individuals that I have that inhabit it.

I highly recommend Rae's book. And I welcome any comments you have about it.

Showing posts with label summer reading series. Show all posts

Showing posts with label summer reading series. Show all posts

Friday, September 25, 2015

Tuesday, September 22, 2015

"Separation Can Be the Worst Thing to Happen"

This summer I have been reading and commenting on the book What If Everybody Understood Child Development? by Rae Pica. These are the last 2 chapters. There will be a summary post later this week.

Chapter 29: "You're Outta Here!"

These chapters deal with two similar ways of dealing with inappropriate behavior - separation. One (time out) is separating a child within the classroom for a period of time. The other (suspension) is separating a child from the school for a period of time.

I found Dr. Haiman's comments about separation very interesting and thought-provoking. He said that "separation is the worst thing that can happen when a child misbehaves." The time of misbehavior is the time when a child needs to be close, not separated. The time alone can be interpreted by children as rejection, say Daniel Siegel and Tina Payne. Time out or the threat of it can increase stress.

I certainly agree with Rae summarizing statement: "As a blanket strategy, time-outs are overused, misused, developmentally inappropriate, and harmful." I've seen teachers use time-out as a first or only strategy when any misbehavior happens within the classroom.

Suspension can be even greater detriment to kids, especially when used with zero tolerance policies. Zero tolerance allows for no assessing the situation, no teaching or learning opportunities, no accounting for kids being kids. It's more concerned about punishment than discipline (teaching).

What instead? Here are some ideas that Rae includes in her chapters:

--Look for ways to give kids a break when they need it. Keep connected to your kids and look for ways to suggest these breaks before behavior is out of control, allowing kids to use breaks for getting themselves under control.

--Use a "time-in." Sit with the child and talk. This can help a child know what to do next time. Or he can express his frustrations to help you better understand what's happening. (This reminds me of Ross W. Greene's Plan B.)

--Allow several different ways for kids to calm down and encourage them to choose the ones they need.

--Use logical consequences instead of suspensions for misbehavior.

--Get to know kids and parents. Understanding a child's situation can help you know how to handle behavior.

Some links from the book---

Friday, September 18, 2015

Threats and Bribes

This summer I'm reading and commenting on the book What If Everybody Understood Child Development? by Rae Pica.

Chapter 27: Bribes and Threats Work, But...

Have you ever been in a position of doing something that just doesn't seem quite right but you're not sure what else to do? Or it's the norm in the surrounding environment and you are expected to do the same? That's been my experience with some classroom management strategies. I've used a behavior chart; it didn't really work. My school has used "behavior bucks" (not their real name but close) that kids could use to "buy" prizes; the same kids always got the bucks and behavior didn't really change overall. Why do teachers, administrators, and schools use these methods? Quick fixes and purchased compliance.

As I thought about this chapter, I remembered the book Lost at School by Ross W. Greene. In that book, he writes that all students know what is the right thing to do and want to do the right thing. Kids that have challenging behavior either have a unsolved problem, a lagging skill, or both. Our jobs as teachers is to help kids solve their problems and develop their skills. These bribe/threat tools reward kids that would have appropriate behavior in any case and cannot help kids who are challenging. (It's a great book; I recommend it.)

As I thought about this chapter, I remembered the book Lost at School by Ross W. Greene. In that book, he writes that all students know what is the right thing to do and want to do the right thing. Kids that have challenging behavior either have a unsolved problem, a lagging skill, or both. Our jobs as teachers is to help kids solve their problems and develop their skills. These bribe/threat tools reward kids that would have appropriate behavior in any case and cannot help kids who are challenging. (It's a great book; I recommend it.)

Chapter 27: Bribes and Threats Work, But...

Have you ever been in a position of doing something that just doesn't seem quite right but you're not sure what else to do? Or it's the norm in the surrounding environment and you are expected to do the same? That's been my experience with some classroom management strategies. I've used a behavior chart; it didn't really work. My school has used "behavior bucks" (not their real name but close) that kids could use to "buy" prizes; the same kids always got the bucks and behavior didn't really change overall. Why do teachers, administrators, and schools use these methods? Quick fixes and purchased compliance.

In this chapter, Rae stresses that, even though teachers/schools use these types of "tools," they are mainly ineffective and have been shown over and over to be ineffective. "Neither...are effective in the long-term for either behavior management or building character and fostering intrinsic motivation," she writes. Rae notes that these types of tools don't work for adults in the workplace either except for simple tasks over a short time frame.

Which is more important, Josh Stumpenhorst asks in the chapter, to have compliant students or engaged learners? I want engaged learners, students who are interested and involved in the classroom. How? Give kids meaningful and worthwhile tasks, provide choice, and create enjoyment in what you are doing.

As I thought about this chapter, I remembered the book Lost at School by Ross W. Greene. In that book, he writes that all students know what is the right thing to do and want to do the right thing. Kids that have challenging behavior either have a unsolved problem, a lagging skill, or both. Our jobs as teachers is to help kids solve their problems and develop their skills. These bribe/threat tools reward kids that would have appropriate behavior in any case and cannot help kids who are challenging. (It's a great book; I recommend it.)

As I thought about this chapter, I remembered the book Lost at School by Ross W. Greene. In that book, he writes that all students know what is the right thing to do and want to do the right thing. Kids that have challenging behavior either have a unsolved problem, a lagging skill, or both. Our jobs as teachers is to help kids solve their problems and develop their skills. These bribe/threat tools reward kids that would have appropriate behavior in any case and cannot help kids who are challenging. (It's a great book; I recommend it.)

I remember one POOR day in my second grade class (poor for me). My most challenging kid was absent as the day started. The morning had been going pretty well. Then my challenging kid came late. At the restroom break, things were a little difficult. As I spoke to get my challenging kid for the fourth (fifth? seventh?) time about hallway behavior, I said (a little exasperated), "Earlier this morning were better." He said, "I know. It's all my fault that now things are bad."

I had to stop and pull him aside. I apologized. I told him that it was not his fault and I was sorry that what I said sounded like that. But I think I was trying to manipulate his behavior through my words. My heart stings even now as I think about that moment. I will not be that teacher again.

Links from the book---

Tuesday, September 15, 2015

Making Meaningful Comments

This summer I'm reading and commenting on the book What If Everybody Understood Child Development? by Rae Pica.

Chapter 26: No More "Good Job!"

Chapter 26: No More "Good Job!"

This chapter, more than others, seems to hit right in the middle of a lot of early childhood teachers. In reading the other chapters, I often think about "those" people who are not around young kids much, making decisions without knowing a lot about early child development.

But this chapter speaks to the everyday preschool teacher, at least many of them.

Rae writes about the automatic response of adults to young kids, when anything happens in the room: "Good job!" The motivation is sincere and good-intentioned; they want to encourage the children and give some positive feedback. But is this really feedback? What are we telling the kids? What did they do that is good? What does good mean? Why was it good? This phrase is not very informative.

And if it is repeatedly said, for no reason other than the child did something (anything), then it isn't very encouraging either. In fact, if kids continue to hear it over and over, they begin to ignore it entirely. And encouraging kids to ignore what I say isn't really what I want to teach.

I've worked hard to try and eliminate this auto-response from my interactions with kids. If it does come out of my mouth, and it still does sometimes, I try to follow it up with a factual statement. "You balanced that larger block on top of the smaller one. That can be difficult to do."

Mostly I just state what I see: "You covered all your paper with the blue paint." This usually leads to the child talking about his painting, telling me what he did to make it or why he covered the whole paper. If not, he will nod at my comment and we both move on. Ellen Ava Sigler, quoted in this chapter, says: "Simply acknowledging a child's work or talking to a child about what they're doing is positive reinforcement."

Another way to talk with kids about their work or their action is to ask questions or encourage discussion: "How did you do that?" "Tell me about this." "It looks like you drew with two markers at the same time. Is that what you did or did you do something else?" These types of statements and questions notice what the child has done and encourage him to talk about it. That can reinforce his work and develop his skills for thinking about what to do next.

I found Rae's comments at the end of the chapter interesting. This constant attempt at building self-esteem can result in kids who have a low tolerance for frustration or failure. Acknowledge when a child makes a mistake or when things don't work out just right. Encourage thinking about what to do instead or acknowledge effort. "You tried to make the blocks stand up but the building fell over. What else could you try?"

Yes we want to encourage kids and their efforts. But we want to communicate meaningfully and honestly. We want to help kids become resilient and self-motivated. Empty comments do little to further those goals.

Some links from the book---

Friday, September 11, 2015

"I'm Still Crafting Here"

This summer I'm reading and commenting on the book What If Everybody Understood Child Development? by Rae Pica.

Chapter 25: In Defense of the Arts

Chapter 25: In Defense of the Arts

This chapter just made me sad. And a little angry. (Well, maybe a lot angry)

Rae tells of a school that canceled a kindergarten show to focus on "college and career ready" activities. The principal/teachers' letter defending the action does nothing to make the situation better. The core of the letter seems to be that canceling the show allows focus on lifelong skills (through becoming strong readers, writers, coworkers, and problem solvers). But I guess the part that really irritates me is this ending: "We are making these decisions with the interests of all children in mind." What? Definitely not the interests of all children. (I might say that the interests of all the children are being underserved by canceling the show, but that's me.) As Rae responds: "Are there not children with the potential and passion to go on to become brilliant chefs, landscape designers, master craftsmen, and architects or to become writers, painters, choreographers, composers and actors? What will happen to their potential and passion when given no soil in which to grow?" Amen. (Go read all of Rae's response to the letter in this chapter. It's great.)

I hear about schools and administrations that cut down time for art, music, and other creative subjects to focus on "academics." It's more important they often say. We have limited time.

Yes, we have limited time. But at my last school, kids spend 2 hours a week in these subjects - 1 hour in art and 1 in music. We can't even allow a fraction of the time to be focused on these more creative pursuits?

I think about my class of second graders that I had. In that classroom, I had students that were great artists. In fact, they often wanted to draw more than anything else. Some of these student were ones that struggled in other areas of school. I tried to find ways to incorporate their strengths in what we were doing--drawing vocabulary words, listening and responding to music in different ways (drawing writing), offering drawing as an option for responding, drawing math problems, sometimes assigning a drawing to everyone as part of what we were doing. While this was not great arts instruction, it was a way to help some of my kids be as successful as possible, recognizing strengths.

Maybe my life as an early childhood educator influenced this approach. In my preschool and kindergarten experiences, we always had art and music and dramatic play as options for learning and exploring. In my church kindergarten class now, there are several ways to explore and express each week. Just this past week, I watched a boy cut and glue paper strips to create his own ideas. He worked for a long time. He started to take his creation to the "take home" table. I pointed out a separate piece he had worked on and asked if he was taking that, too. He turned back to the table and worked to incorporate that into his creation. Then he began to add more to what he had done. As we talked about it, he said, "I'm still crafting here."

I worry about those kids who relate to music or art or acting or dance. Where are the places that they can excel, that they can be the best and use their strengths? Are we pushing out those opportunities in the name of academic success? Maybe we should use them to enhance academic success.

Or maybe not. Art and music and drama and dance are valuable pursuits in their own right. We should pursue these to help us think creatively. We should do these things because they are fun. And they can help make well-rounded people for the future of our society.

Some links from the book---

Labels:

art,

music,

summer reading series

Wednesday, September 9, 2015

Another Book Study

I've been reading and commenting on the book What If Everybody Understood Child Development? by Rae Pica. (Here's a list of my reading so far.)

Early Childhood and Youth Development is also reading the book (in groups of chapters) and asking various experts to comment on them. This book study started last week, so there's still time to get "caught up." There's been lots of discussion on the first post.

August 31: Chapters 1, 2, 7 (Angèle Sancho Passe)

September 7: Chapters 3, 5 (Gwen Simmons)

I have enjoyed every word of this book. If lots of educators read it and think about the issues in it, we will be having lots of new discussions about young kids and learning.

And who wouldn't welcome that.

Early Childhood and Youth Development is also reading the book (in groups of chapters) and asking various experts to comment on them. This book study started last week, so there's still time to get "caught up." There's been lots of discussion on the first post.

August 31: Chapters 1, 2, 7 (Angèle Sancho Passe)

September 7: Chapters 3, 5 (Gwen Simmons)

I have enjoyed every word of this book. If lots of educators read it and think about the issues in it, we will be having lots of new discussions about young kids and learning.

And who wouldn't welcome that.

Tuesday, September 8, 2015

Why Homework?

This summer I'm reading and commenting on the book What If Everybody Understood Child Development? by Rae Pica.

Chapter 24: The Homework Debate

When I was in school, I loved homework. I know, that's weird. But I loved school and I loved learning. If I didn't have homework, I would read and read and read. I would look up words to find out their meanings. Sometimes...I even practiced math problems on my chalkboard at home.

Chapter 24: The Homework Debate

When I was in school, I loved homework. I know, that's weird. But I loved school and I loved learning. If I didn't have homework, I would read and read and read. I would look up words to find out their meanings. Sometimes...I even practiced math problems on my chalkboard at home.

My brother did not like homework. He wanted to explore the wilds of our backyard and later beyond. He would ride his bike up and down the side streets. He did not want to be sitting at a table, figuring out fractions or writing essays.

I thought about our different interests and reactions to school work as I read this chapter. And I came back to a question that I've been pondering about lots of things lately - WHY? Why do teachers give homework? What is the purpose?

"The research clearly shows no correlation between academic achievement and homework in elementary school," Rae Pica writes. But isn't that why teachers are assigning it? To give practice, to increase proficiency and fluency? To help kids achieve?

And homework can be a determent to achievement. Kids stop reading for pleasure because they associate reading with work and not with enjoyment. Homework can increase stress, tantrums, and physical ailments. I've heard stories about 8-year-olds working on homework assignments for hours. And this after being in school all day.

All this time with homework reduces downtime. Time for kids to explore their own interests. Time for kids to be outside. Time to relax.

I didn't give much homework when I was in the classroom. At my last school, I found it was a waste of effort. Many kids had little support at home to get homework done. I spent lots of time chasing down work or reminding kids of it. I asked myself why I was assigning it. And looked for more effective ways to meet those goals.

I encouraged kids to read at home each night. I urged them to check out library books. I provided books in my classroom that they could take home. (Some of those are still at students' homes!) Reading lots of different texts (especially ones you choose yourself) is a great way to build vocabulary, increase fluency and comprehension, and build skills for later achievement. Did all of them read every night? No. But they wouldn't have done lots of homework either.

As "homework," encourage kids to develop a skill or follow an interest. If a kid is like I was, he will read or explore more math or create science experiments--all "academic" pursuits. Other kids will paint pictures or climb trees or make a map of a buried treasure in the neighborhood. These activities can help the kid think and relax and be better prepared for the next school day.

Each teacher must assess his own class, community, and philosophy. Each teacher must make a decision about what is effective for his students and what strategies and techniques he will use. Homework is one of those things. But we must make sure we aren't doing it just because it is expected, the thing that teachers do. We must be intentional about everything in the classroom...especially those that happen outside the school doors.

Some links from the book---

- End Homework Now

- Homework: A Necessary Evil? Surprising Findings from New Research

- How Much Homework Is Too Much?

And a few more---

- My Issues with Homework

- A Creative Solution to the Homework Wars

- What Happened When Our School Stopped Assigning Nightly Homework? More Learning!

Thursday, September 3, 2015

To Plug In or Not Plug In?

This summer I'm reading and commenting on the book What If Everybody Understood Child Development? by Rae Pica.

Chapter 21: Should We Teach Handwriting in the Digital Age?

Chapter 22: Just Say "No" to Keyboarding in Kindergarten

Chapter 23: iPads or Play Dough?

These three chapters focused on issues related to technology and young children. As Rae Pica states in the book, the opinions on this larger topic run the gamut--from those who advocate full-on technology usage in the youngest classrooms to those who think all electronics should be banned for young kids.

Some say that we should be teaching those keyboarding skills to kids since they will use them their entire lives. Handwriting is obsolete or soon will be, they say. Kids can communicate their ideas more completely using technology since they don't have think about letter formation or stamina in writing. Technology is better because kids can focus on the ideas rather than the mechanics.

While I agree that some kids struggle with the physical demands of handwriting, I do think that kids (and adults) lose something when writing on a computer rather than by hand. When writing by hand, the writer can ponder and make a more physical connection with what is written. Ideas percolate more and can be refined before being put down on paper.

Using more technology often leads to less physical activities and less exploration with "real world" materials. While kids may love using screens for all kinds of things, they also enjoy and learn more from using their senses, moving their bodies, and handling all kinds of things. More understanding of trial and error, cause and effect, and learning from failure happens when kids are using a variety of materials and exploring and experimenting.

I think too often we see technology as THE answer. Technology (just like play dough or blocks or paint and brushes) is a tool that can aid a child's learning and pique his curiosity. I think technology should be just one part of what happens in a child's life. As with anything that comes into the classroom, it should be used intentionally and judiciously.

I would advocate a balanced and reasoned approach. Technology exists in the world of kids and should be a part of the classroom. But when it's used, it should be purposeful and intentional. It should fit with the play dough and crayons and dolls and dishes. It should follow the child's lead and interest. It should be part of the authentic learning that's happening in the classroom.

P.S. A personal peeve: "They'll need it later so we should give it to them now." Let's teach who our kids are now, not who they will be or what they might become. Let's give them what they need now. And give them what they need later when it is later.

Some links from the book---

Chapter 21: Should We Teach Handwriting in the Digital Age?

Chapter 22: Just Say "No" to Keyboarding in Kindergarten

Chapter 23: iPads or Play Dough?

These three chapters focused on issues related to technology and young children. As Rae Pica states in the book, the opinions on this larger topic run the gamut--from those who advocate full-on technology usage in the youngest classrooms to those who think all electronics should be banned for young kids.

Some say that we should be teaching those keyboarding skills to kids since they will use them their entire lives. Handwriting is obsolete or soon will be, they say. Kids can communicate their ideas more completely using technology since they don't have think about letter formation or stamina in writing. Technology is better because kids can focus on the ideas rather than the mechanics.

While I agree that some kids struggle with the physical demands of handwriting, I do think that kids (and adults) lose something when writing on a computer rather than by hand. When writing by hand, the writer can ponder and make a more physical connection with what is written. Ideas percolate more and can be refined before being put down on paper.

Using more technology often leads to less physical activities and less exploration with "real world" materials. While kids may love using screens for all kinds of things, they also enjoy and learn more from using their senses, moving their bodies, and handling all kinds of things. More understanding of trial and error, cause and effect, and learning from failure happens when kids are using a variety of materials and exploring and experimenting.

I think too often we see technology as THE answer. Technology (just like play dough or blocks or paint and brushes) is a tool that can aid a child's learning and pique his curiosity. I think technology should be just one part of what happens in a child's life. As with anything that comes into the classroom, it should be used intentionally and judiciously.

I would advocate a balanced and reasoned approach. Technology exists in the world of kids and should be a part of the classroom. But when it's used, it should be purposeful and intentional. It should fit with the play dough and crayons and dolls and dishes. It should follow the child's lead and interest. It should be part of the authentic learning that's happening in the classroom.

P.S. A personal peeve: "They'll need it later so we should give it to them now." Let's teach who our kids are now, not who they will be or what they might become. Let's give them what they need now. And give them what they need later when it is later.

Some links from the book---

- Why Learning to Write by Hand Matters

- Why Handwriting Still Matters in the Digital Age

- Is Teaching Keyboarding in Kindergarten Developmentally Appropriate

- How Much Technology in the Classroom Is Too Much?

- Is Technology Sapping Children's Creativity?

And a few more---

Friday, August 28, 2015

Failing at Failure

This summer I'm reading and commenting on the book What If Everybody Understood Child Development? by Rae Pica.

Chapter 20: Failure Is an Option

Do you remember a time when you made a mistake or failed at something? How did you feel? What did you learn? Looking back, do you wish it never happened or are you glad it did?

Today in many classrooms, students are worried about failing. Not failing a subject or failing a test. They are worried about making a mistake or not coming in first.

Many homes cultivate this anxiety. Parents try to protect children from making a mistake (or suffering consequences of a mistake). They don't want the child to feel bad or have a negative experience or not be successful. But that's not the way life will treat them.

Schools cultivate this anxiety. Get it right. There's only one right answer. A bad grade will reflect on your entire educational career. Your teacher will be disappointed. If you don't do well, your teacher may lose her job. Now that's pressure.

But the lack of failure can result in a lack of resiliency, the ability to recover from discouragement or adversity. The lack of failure or the fear of it can result in less risk-taking, less willingness to try something new, less experimenting to solve a problem. Kids will stick with what they know will work so they will be "right."

Rae Pica mentions Carol Dweck (someone I've been hearing a lot about lately). Dweck has proposed a theory that an individual's mindset impacts what he does. A fixed mindset believes that intelligence and abilities are predetermined and unchangeable so the individual works hard to prove (and defend and not push the limits of) his intelligence. A growth mindset believes that intelligence and talent can be developed with effort, so the individual will work to increase his abilities, often making mistakes along the way.

I've heard kids in my church kindergarten class ask, "What do we do here?" I think that can be attributed to doing things the "right way" and not making a mistake. I've been in a classroom of second graders, silent because no one wants to hazard an answer to the question I've just asked. I've seen kids upset because someone else came in first. it can be disappointing to lose but kids need to learn that they cannot always come out on top. And if they worked hard and tried their best, they did what they could do. And they can work harder to improve.

Everyone wants to be a winner, a success, the one on top. But, really, who learns the most? One who can breeze through? Or one who works hard and maybe even fails? I learn the most when I fail (even if I wish I succeeded). I want to keep trying different things, to take risks in my teaching and learning.

We want kids who work hard and try to improve, who take risks and experiment to solve problems. Kids who fail and keep at it.

Some links from the book---

Chapter 20: Failure Is an Option

Do you remember a time when you made a mistake or failed at something? How did you feel? What did you learn? Looking back, do you wish it never happened or are you glad it did?

Today in many classrooms, students are worried about failing. Not failing a subject or failing a test. They are worried about making a mistake or not coming in first.

Many homes cultivate this anxiety. Parents try to protect children from making a mistake (or suffering consequences of a mistake). They don't want the child to feel bad or have a negative experience or not be successful. But that's not the way life will treat them.

Schools cultivate this anxiety. Get it right. There's only one right answer. A bad grade will reflect on your entire educational career. Your teacher will be disappointed. If you don't do well, your teacher may lose her job. Now that's pressure.

But the lack of failure can result in a lack of resiliency, the ability to recover from discouragement or adversity. The lack of failure or the fear of it can result in less risk-taking, less willingness to try something new, less experimenting to solve a problem. Kids will stick with what they know will work so they will be "right."

Rae Pica mentions Carol Dweck (someone I've been hearing a lot about lately). Dweck has proposed a theory that an individual's mindset impacts what he does. A fixed mindset believes that intelligence and abilities are predetermined and unchangeable so the individual works hard to prove (and defend and not push the limits of) his intelligence. A growth mindset believes that intelligence and talent can be developed with effort, so the individual will work to increase his abilities, often making mistakes along the way.

I've heard kids in my church kindergarten class ask, "What do we do here?" I think that can be attributed to doing things the "right way" and not making a mistake. I've been in a classroom of second graders, silent because no one wants to hazard an answer to the question I've just asked. I've seen kids upset because someone else came in first. it can be disappointing to lose but kids need to learn that they cannot always come out on top. And if they worked hard and tried their best, they did what they could do. And they can work harder to improve.

|

| My rope light FAIL |

Everyone wants to be a winner, a success, the one on top. But, really, who learns the most? One who can breeze through? Or one who works hard and maybe even fails? I learn the most when I fail (even if I wish I succeeded). I want to keep trying different things, to take risks in my teaching and learning.

We want kids who work hard and try to improve, who take risks and experiment to solve problems. Kids who fail and keep at it.

Some links from the book---

- Victims of Excellence: Teaching Children to Learn from Mistakes, Parents to Allow Them

- The Dangers of Praising Children Inappropriately

- It's a Mistake Not to Use Mistakes As Part of the Learning Process

And a few more---

Friday, August 21, 2015

This Is a Test (Unfortunately)

This summer I'm reading and commenting on the book What If Everybody Understood Child Development? by Rae Pica.

Chapter 19: The Trouble with Testing

In education today, students must endure a plethora of standardized testing. According to one study, the average student is tested once a month (and may be tested up to twice a month)! That's a lot of number 2 pencils.

Testing has become the "to go" option, the way to find out how schools/teachers are doing and what is working or not working. The problem? Testing itself doesn't work. Standardized tests are terrible predictors of educational success or intelligence. Testing doesn't reveal or promote divergent, independent, creative thinking.

Rae Pica writes: "Standardized tests do not require the understanding, creative thinking, analysis, synthesis, or application of information that are the hallmarks of in-depth thinking (you know, the kind we need to continue to innovate and prosper.)"

Tests amp up everyone's anxiety. Students are anxious about taking the test (especially when it's been communicated HOW IMPORTANT it is). Parents and teachers are anxious about the effects and atmosphere for the children. And then, when the results come in, more anxiety.

The problem with those results? Little can be extrapolated from them. A test only shows a snapshot of the student at that moment in time. If the test had been on a different day or a different time of day, if the student had a different start to his day or the room had been different - if any of these things had been different, the results may have been different. A test is only a snapshot of a moment. How can we base so many decisions and conclusions on a snapshot.

A couple of years ago, my second grade class was taking a practice test, to prepare for the "real" test. We had to sit for a hour (at least), in silence, working in a booklet to complete the test. One boy sat at a table and was making some noise and not working. I went to him to talk and get him back on task. As we talked, he said, "I just can't do this. I'm not smart. I can't." That's the trouble with testing.

Some links from the book---

Chapter 19: The Trouble with Testing

In education today, students must endure a plethora of standardized testing. According to one study, the average student is tested once a month (and may be tested up to twice a month)! That's a lot of number 2 pencils.

Testing has become the "to go" option, the way to find out how schools/teachers are doing and what is working or not working. The problem? Testing itself doesn't work. Standardized tests are terrible predictors of educational success or intelligence. Testing doesn't reveal or promote divergent, independent, creative thinking.

Rae Pica writes: "Standardized tests do not require the understanding, creative thinking, analysis, synthesis, or application of information that are the hallmarks of in-depth thinking (you know, the kind we need to continue to innovate and prosper.)"

Tests amp up everyone's anxiety. Students are anxious about taking the test (especially when it's been communicated HOW IMPORTANT it is). Parents and teachers are anxious about the effects and atmosphere for the children. And then, when the results come in, more anxiety.

The problem with those results? Little can be extrapolated from them. A test only shows a snapshot of the student at that moment in time. If the test had been on a different day or a different time of day, if the student had a different start to his day or the room had been different - if any of these things had been different, the results may have been different. A test is only a snapshot of a moment. How can we base so many decisions and conclusions on a snapshot.

A couple of years ago, my second grade class was taking a practice test, to prepare for the "real" test. We had to sit for a hour (at least), in silence, working in a booklet to complete the test. One boy sat at a table and was making some noise and not working. I went to him to talk and get him back on task. As we talked, he said, "I just can't do this. I'm not smart. I can't." That's the trouble with testing.

Some links from the book---

- How to End Over-Testing in School: Kids Should Answer Only Half the Questions

- Testing 1, 2, 3: Accountability Run Amok

- Ten Ways to Make Test Prep Fun

And a few more---

Friday, August 14, 2015

What's Authentic Learning?

This summer I'm reading and commenting on the book What If Everybody Understood Child Development? by Rae Pica.

Chapter 17: In Defense of Authentic Learning

Chapter 18: Who Should Lead the Learning?

Rae Pica asks, "Who wouldn't want children to have real, genuine learning?" Maybe everyone wants real learning to happen, but it comes down to how we define learning. Emphasis too often is placed on remembering and recalling facts and data. But memorization isn't learning.

In today's world, it is easy to find specific information. A quick online search yields a variety of results. What is needed is more discernment, more analyzing of that information. Leaders and workers of tomorrow need to evaluate situations and solve problems. "65 percent of current elementary school students will end up doing jobs that have yet to be invented." How is memorizing data going to prepare students for that?

We need to help kids begin to explore and think independently. We should release control of the learning and follow the interests and needs of kids. Yes, we need to make sure kids are learning those standards (broad statements of understanding), but we can let them choose how to get there. We need to let them do more, explore more, choose more. Why? Because one day they will not have someone to supply answers. They will need to be motivated to find out on their own. And we can help them do that now.

I remember once when I failed at this. (Well, let's face it, there have been quite a few times. But this instance stands out in my mind.) Teaching first grade, I was trying to encourage kids to wonder and think about things. I created a wonder wall. Kids would write down things they were wondering about (questions or topics) and put them on the wall. Occasionally, we would remove a few and talk about them. Sometimes the questions were about me. ("I wonder why Mr. Wiley wants to be a teacher.") Sometimes the questions were general knowledge or specific interests. Sometimes they were more philosophical.

In one of our "sessions," I read this question: "I wonder where rainbows come from." I read the question to my first graders. I encouraged them to think about and offer answers. We talked a great deal about their speculations. Then I explained the scientific answer - light shining through raindrops separates into the spectrum of colors. We talked more about it. (I even drew pictures.) We moved on to other things.

On my drive home that day, I realized that I FAILED as a teacher. Well, maybe that's a strong word but that's what I thought. I should have encouraged them to do some research for the answer. I could provide resources for them to discover the answer. We could have had a study of several days (or more) that would have been completely student generated and hopefully student led. I failed.

One thing is certain. I won't make that mistake again. Authentic learning is meaningful and connected to the student's life. How can we create that regularly for students, no matter what age or grade level they are?

Some links from the book---

Friday, August 7, 2015

They Need More Than Just Literacy and Numeracy

This summer I'm reading and commenting on the book What If Everybody Understood Child Development? by Rae Pica.

Chapter 14: The Body Matters, Too

Chapter 15: Reading, Writing, 'Rithmetic...and Recess

Chapter 16: Why Kids Need "Gym"

In previous chapters, Rae Pica has noted that many educators or reformers treat the body and the brain as separate. At least they behave in ways that support this dichotomy. Teachers focus on literacy and numeracy but not physicality.

But the body is important, too. Young kids are developing serious health problems, mainly because they do not have the opportunities to run, play, and move as in the past. As teachers, we must think about the physical skills and health needs of kids as well as their reading/math skills and cognitive needs.

How can teachers do this? Look for ways to incorporate movement in each day. Include brain breaks and other opportunities for movement as part of instruction. Teach some basic movement skills and add unplanned, self-selected movement activities as part of the schedule.

Unplanned, self-selected activities = recess. Many schools are eliminating or at least paring down time for recess. Exclusion from recess is an oft-used tool for behavior management. (And usually effects the kids that need recess the most!) Rae Pica notes several benefits for including recess as a part of the school day--breaks in learning actually benefit learners; on-task attention increases when recess is a part of the schedule; physical activity feeds the brain with more oxygen, water, and glucose; recess is a great stress-reducer; unstructured play helps build social skills.

When I was teaching second grade, we did go out for recess. Many days but not every day. I noticed the students. Kids would run and jump, climb and swing. They would create chasing and tagging games. I noticed the teachers. Many would sit along the sidelines and chat. They would call to kids to "stop that" or "change this." This time was seen as just a time to let the kids go and make sure they didn't get hurt.

But I think that this can be an important time of instruction, too. Not with planned and specific things for kids to do. But for encouragement. For suggestions of things to try. For interaction and conversation in ways that don't happen in the classroom. And sometimes running and jumping, too.

As teachers, we are responsible for the whole child. Brain and body. Look for ways to nurture both.

Some links from the book---

- Solving the Growing Physical Inactivity Crisis

- Why Recess Matters, How to Defend It

- Withdrawing Recess As Punishment. Does It Work?

- Why Play Time Is Not Break Time

And a few others---

Friday, July 31, 2015

The P Word

This summer I'm reading and commenting on the book What If Everybody Understood Child Development? by Rae Pica.

Chapter 13: "Play" Is Not a Four-Letter Word

Chapter 13: "Play" Is Not a Four-Letter Word

"He's just playing."

"Quit that playing. Do something productive."

"Be serious. Stop playing."

Maybe you've heard phrases like these in adult interactions. Maybe even in connection with preschoolers and children.

Kids are born to play. Play is their job, their occupation.

If that's so, why are so many adults trying to do something else with them?

In this chapter, Rae Pica looks at the push for achievement and accomplishment at the expense of play. "Got to get those kids ready for the real world." But isn't the real world all about problem-solving and exploring solutions? Isn't it about thinking and assessing and doing? All of those things are related to play, especially for younger children.

Rae writes regarding play: "Among the social skills learned are the ability to share, cooperate, negotiate, compromise, make and revise rules, and to take the perspectives of others." Play also helps develop problem-solving, helps kids deal with stress and cope with fears, and develop literacy, math, and creative skills. And much more.

In schools today, adults often tell kids how to use materials or what exactly to do. Too often in my church classroom, a kindergartner will walk up and ask: "What do we do here?" My current response to this: "Look at the materials. What do you think you could do?"

I set up situations and materials in my classroom to suggest ways kids may play, work, and interact. But they should explore and experiment on their own. Recently I set up chairs and a steering wheel as a car. Kids began to drive to various locations and negotiate where to sit. The vehicle needed to be expanded, so we added a couple of chairs. Eventually our vehicle was a large van or bus, allowing seven kids to riding and play at the same time. (The doll made an eighth passenger.)

Kids played out various roles. They used conversation skills. They challenged preconceived ideas. ("A girl is driving?") They discussed any minor conflicts that arose...and involved me when they felt it may be needed. ("Mr. Scott, they are making the baby pee out of the window.")

Play is so important. True play, not directed or orchestrated by adults, is the way that children truly work out their understandings about the world.

And, as Rae says: "I shouldn't have to defend play for children any more than I should have to defend their eating, sleeping, and breathing."

Some links from the book---

Friday, July 24, 2015

Kids' Preferred Mode of Learning

This summer I'm reading and commenting on the book What If Everybody Understood Child Development? by Rae Pica.

Chapter 12: In Defense of Active Learning

For a while, I worked in a publishing company with a lot of other folks. Periodically our company would upgrade software or systems. A lot of people would need to know about the new system and how to use it. So the company would schedule training sessions.

Often these sessions consisted of a large group of people sitting in a room watching someone talk about the features and how to do it while clicking things on screen. While this may be a way to disseminate information to a lot of people in an efficient way, it was not an effective way for me to learn what to do with the new system. The best way for me to know what to do and how to do it was to play with the system on my computer. Working my way through examples and trying new things.

Rae Pica talks about these two types of learning in this chapter. Explicit learning (hearing something) and implicit learning (doing something) are both used in classrooms today. However, there is a lot less doing, active learning, than in the past. But discovery and exploration yield more lasting and mor meaningful learning than hearing or reading information. Rae reminds us that movement is the young child's preferred mode of learning and we should use that preference as a way to teach. That is most effective.

One example she gives: a preschool teacher conducted a mock lesson on kiwi fruit with parents. Half of the parents were told about kiwis and given an coloring sheet with brown and green crayons. The other half took a field trip to the hallway and explored a tree with kiwi; they could explore the fruit with their senses. The latter group left with greater understanding of kiwis. Experience and exploration gave much more meaning than listening.

I had a similar experience when I moved to Tennessee. My first fall season, I saw trees begin to change to vibrant reds and yellows and oranges. I had learned about fall when I was a kid. I had seen pictures of colorful trees. I had seen people in movies walk along colorful avenues in autumn. But my home in Texas did not have this type of fall. So I "knew" about fall as a season but that was it. In Tennessee I experienced it. That first year, my wife and I drove around the town, looking for different colored trees. We compared how they looked. We gathered a few leaves and pressed them in books to save. I really knew about fall leaves when I experienced and explored it.

How can we give learning opportunities to kids? How can we actively involve them in whatever we are teaching? How can we use their preferred mode of learning--movement--to make those learning connections?

Rae has challenged me to look for ways to make all kinds of learning experiential and active. And maybe to start dreaming again.

Some links from the book---

Chapter 12: In Defense of Active Learning

For a while, I worked in a publishing company with a lot of other folks. Periodically our company would upgrade software or systems. A lot of people would need to know about the new system and how to use it. So the company would schedule training sessions.

Often these sessions consisted of a large group of people sitting in a room watching someone talk about the features and how to do it while clicking things on screen. While this may be a way to disseminate information to a lot of people in an efficient way, it was not an effective way for me to learn what to do with the new system. The best way for me to know what to do and how to do it was to play with the system on my computer. Working my way through examples and trying new things.

Rae Pica talks about these two types of learning in this chapter. Explicit learning (hearing something) and implicit learning (doing something) are both used in classrooms today. However, there is a lot less doing, active learning, than in the past. But discovery and exploration yield more lasting and mor meaningful learning than hearing or reading information. Rae reminds us that movement is the young child's preferred mode of learning and we should use that preference as a way to teach. That is most effective.

One example she gives: a preschool teacher conducted a mock lesson on kiwi fruit with parents. Half of the parents were told about kiwis and given an coloring sheet with brown and green crayons. The other half took a field trip to the hallway and explored a tree with kiwi; they could explore the fruit with their senses. The latter group left with greater understanding of kiwis. Experience and exploration gave much more meaning than listening.

I had a similar experience when I moved to Tennessee. My first fall season, I saw trees begin to change to vibrant reds and yellows and oranges. I had learned about fall when I was a kid. I had seen pictures of colorful trees. I had seen people in movies walk along colorful avenues in autumn. But my home in Texas did not have this type of fall. So I "knew" about fall as a season but that was it. In Tennessee I experienced it. That first year, my wife and I drove around the town, looking for different colored trees. We compared how they looked. We gathered a few leaves and pressed them in books to save. I really knew about fall leaves when I experienced and explored it.

How can we give learning opportunities to kids? How can we actively involve them in whatever we are teaching? How can we use their preferred mode of learning--movement--to make those learning connections?

Rae has challenged me to look for ways to make all kinds of learning experiential and active. And maybe to start dreaming again.

Some links from the book---

- Identifying and Nurturing the Intelligence of Movement

- Making Stories Come Alive

- Bringing the Body to Digital Learning

And a few more---

Friday, July 17, 2015

If the Bum Is Numb

This summer I'm reading and commenting on the book What If Everybody Understood Child Development? by Rae Pica.

Chapter 10: The Myth of the Brain/Body Dichotomy

Chapter 11: Why Does Sitting Still Equal Learning?

How do you feel when you sit all day? Maybe you're in a meeting or a conference or just at home. Sitting all day can make you really tired. And yet, as Rae Pica says, we expect kids to do it all day while they are learning.

We've bought into the assumption that the body and the brain are separate entities. We want to teach the brain and ignore the body. We limit recess or PE or other times when the body is fully engaged. We equal sitting and listening to learning. Or at least to effective teaching.

Rae quotes teacher Dee Kalman: "When the bum is numb, the mind is dumb."

The brain is more active when the body is moving. Blood is flowing and chemicals for long-term memory and focus increase. Sitting for more than short periods of time (more than 10 minutes) causes us to begin to lose focus and awareness. 10 minutes!

I've seen it in the classroom. When I taught first graders, we had to have stand up breaks, movement breaks, and even dance breaks. We would move for a short while and then get back to other things. One of our favorite games was Move, Freeze, Add! In my second grade class, we would have "roving practice." Kids would move to a place in the room and spell a word (or solve math equation). Then they would move to a new place to write down their word or math solution. We did this for several minutes. In both classes, I would often tell them to find a partner and we would work together while standing up. Sometimes we would switch partners often.

The younger the kids or the more challenging the thinking, the more need there is to incorporate learning.

Think about easy ways to add movement. At the very least, incorporate brain breaks at regular intervals. Make sure they move across the midline (right hand moving to left side and vice versa). This wakes up the brain.

Keep on moving!

Some links from the book--

Chapter 10: The Myth of the Brain/Body Dichotomy

Chapter 11: Why Does Sitting Still Equal Learning?

How do you feel when you sit all day? Maybe you're in a meeting or a conference or just at home. Sitting all day can make you really tired. And yet, as Rae Pica says, we expect kids to do it all day while they are learning.

We've bought into the assumption that the body and the brain are separate entities. We want to teach the brain and ignore the body. We limit recess or PE or other times when the body is fully engaged. We equal sitting and listening to learning. Or at least to effective teaching.

Rae quotes teacher Dee Kalman: "When the bum is numb, the mind is dumb."

The brain is more active when the body is moving. Blood is flowing and chemicals for long-term memory and focus increase. Sitting for more than short periods of time (more than 10 minutes) causes us to begin to lose focus and awareness. 10 minutes!

|

| Dance break! |

The younger the kids or the more challenging the thinking, the more need there is to incorporate learning.

Think about easy ways to add movement. At the very least, incorporate brain breaks at regular intervals. Make sure they move across the midline (right hand moving to left side and vice versa). This wakes up the brain.

Keep on moving!

Some links from the book--

- Understanding the Child's Mind/Body Connection

- Can Exercise Close the Achievement Gap?

- Moving with the Brain in Mind

- Teaching Children Who Just Won't Sit Still

And a few more--

Friday, July 10, 2015

Thinking About the Learning Environment

This summer I'm reading and commenting on the book What If Everybody Understood Child Development? by Rae Pica.

Chapter 8: "But Competition Is Human Nature"

Chapter 9: Terrorist Tots?

As I read these two chapters, I kept thinking about society - the issues in these chapters are related to societal concerns invading the learning environment. Both of these issues relate again to kids' needs and how the teacher can create an environment that meets those needs in appropriate and adequate ways.

"Kids need to know how to survive in our competitive world." This sums up some of the comments related to this issue. But Rae questions whether it's really true. Is our world that competitive? Most of the examples we can think of (college placement, job positions) are really instances when the individual must present their best efforts. Someone chooses who is in and who is out based on a variety of criteria (most of it unknown). Being competitive has little impact on the final result.

Make games into challenges rather than competitions. Race against a timer instead of one another. Work to solve a problem rather than compete for it. Work together to build the tallest secure tower rather than compete with one another to create a tall tower. Celebrate finishing rather than winning. Yes, kids will face competition as they get older. They will face winning and losing. But maybe, at this early time of life, we can focus on the enjoyment of playing or solving rather than collating points to "beat" someone else.

Employers want adults who can work in teams; communities want members who can work for common goals. Helping kids learn how to work together--and to work out differences in cooperative ways--are skills that will benefit them throughout their lives.

The other chapter issue is one that can be very sensitive. We want to have safe learning environments. But zero-tolerance policies regarding violent play and gun play can be more harmful than helpful. Fantasy play with superheroes, guns, and "violence" can help kids work through feelings and anxieties about things happening in our world. Banning that kind of play can create more anxieties and less capable children.

We as teachers can allow this play with guidelines and boundaries (at certain times and in certain areas). Make sure kids know how to "opt out" of this play, telling others they don't want to be a part of the game (at the onset or anytime during the game). Talk with kids about their ideas for play and help them expand their ideas for these scenarios. Maybe talk about how to cooperate to solve problems or encourage them to think about why different parties act in those ways.

Some links from the book---

Chapter 8: "But Competition Is Human Nature"

Chapter 9: Terrorist Tots?

As I read these two chapters, I kept thinking about society - the issues in these chapters are related to societal concerns invading the learning environment. Both of these issues relate again to kids' needs and how the teacher can create an environment that meets those needs in appropriate and adequate ways.

"Kids need to know how to survive in our competitive world." This sums up some of the comments related to this issue. But Rae questions whether it's really true. Is our world that competitive? Most of the examples we can think of (college placement, job positions) are really instances when the individual must present their best efforts. Someone chooses who is in and who is out based on a variety of criteria (most of it unknown). Being competitive has little impact on the final result.

Make games into challenges rather than competitions. Race against a timer instead of one another. Work to solve a problem rather than compete for it. Work together to build the tallest secure tower rather than compete with one another to create a tall tower. Celebrate finishing rather than winning. Yes, kids will face competition as they get older. They will face winning and losing. But maybe, at this early time of life, we can focus on the enjoyment of playing or solving rather than collating points to "beat" someone else.

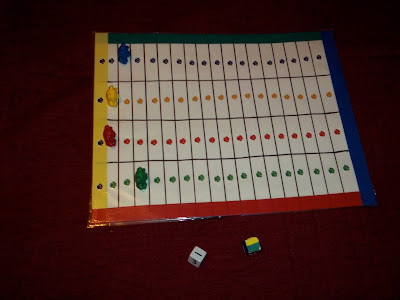

|

| In this game, every player moves whatever colored marker comes up. The group works together to get the bears to the end of the path. |

The other chapter issue is one that can be very sensitive. We want to have safe learning environments. But zero-tolerance policies regarding violent play and gun play can be more harmful than helpful. Fantasy play with superheroes, guns, and "violence" can help kids work through feelings and anxieties about things happening in our world. Banning that kind of play can create more anxieties and less capable children.

We as teachers can allow this play with guidelines and boundaries (at certain times and in certain areas). Make sure kids know how to "opt out" of this play, telling others they don't want to be a part of the game (at the onset or anytime during the game). Talk with kids about their ideas for play and help them expand their ideas for these scenarios. Maybe talk about how to cooperate to solve problems or encourage them to think about why different parties act in those ways.

Some links from the book---

- Creating a Non-Competitive Climate for Children

- The Case Against Competition

- War, Gun, and Superhero Play. Good or Bad?

- What's a Teacher to Do? Superhero Play

And a few more---

Saturday, July 4, 2015

Giving Them What They Need

This summer I'm reading and commenting on the book What If Everybody Understood Child Development? by Rae Pica.

Chapter 6: Teaching Girls They're More Than a Pretty Face

Chapter 6: Teaching Girls They're More Than a Pretty Face

Chapter 7: Doing Away with "Baby Stuff"

These two chapters made me immediately think of needs. Are we giving kids what they need? Are we doing things that meet our own needs or the needs of the school instead of the needs of the kids?

Rae Pica discusses how adults comment more often on a girl's appearance when meeting. They will say that the girl looks cute/pretty/nicely dressed. So girls begin to internalize that appearance is what matters, that how they look determines who they are. All around us the culture also conveys the importance of how you look, especially to girls. As adults we need to talk with girls about their interests or activities. We should comment on other aspects of her life rather than appearance.

Rae also discusses the "baby stuff" that many education leaders have decided is unessential - nap time. Presumably, dropping nap time allows for more academic time. But kids who are tired have higher behavior problems or have lower abilities to learn or perform. As Rae Pica writes: "We talk so much about preparing kids for school but give very little thought to preparing schools for kids." As teachers, we may not be able to instigate a time for naps, but we can remember that our young learners will get tired and plan activities accordingly. Schedule high performance times earlier and more relaxing activities later in the day.

Overall, we need to think about the kids and their needs. Girls need to feel valued and connected. All young kids need rest and downtime. How we think about and plan for those needs makes all the difference. Too often adults tend to think about their own needs or comfort zones. It may be difficult to suppress a tendency to comment on a girl's appearance. It may be challenging to slow down to engage tired learners. But we should look for ways to focus on what's best for kids, to prepare the learning environment for kids rather than just focus on preparing kids for the learning experience.

Sunday, June 28, 2015

Hug or No Hug?

This summer I'm reading and commenting on the book What If Everybody Understood Child Development? by Rae Pica.

Chapter 5: When Did a Hug Become a Bad Thing?

Schools are concerned about kids' safety so they instigate 'no touch' policies. This reminds me a little of the previous chapter about bubble wrapping kids. Anxiety is high so, to create the really necessary safe classroom, the pendulum swings to no touch at all.

Touch is important for kids' development. As Rae Pica mentions, "children need physical contact in order to thrive and grow in every aspect of development." Social skills, emotional skills, and even physical development are impacted by contact with others.

As a male teacher with young kids, this particular issue is very real. The few times I have been in a room with a child alone, the door is always open and we are always in full view. I will hug a kid, if he or she initiates it, but it's quick. I often give high fives, fist bumps, and a quick pat on the back. In my second grade class, the kids left at the end of the day by giving me a fist bump as they left. It was out last ritual and our way to contact. And it helped us regroup and connect, no matter how the day had gone. But if a child is upset and needs some comfort, I give whatever is needed - a hand around the shoulders, a hug, a pat on the back.

We need to help kids know how to interact with one another in ways that are satisfying and appropriate. A few years ago, I taught in a 2-year-old class. One boy didn't interact with other kids anytime except in our classroom. He would bang into other kids, almost tackle them when he saw them, and so forth. Other kids were unsure what to do. They didn't like some of the things he was doing. But he didn't know how to interact with them when he was excited to see them. We worked on ways to help him interact in less "rough" ways unless the other kid wanted that.

Rae Pica also mentions that we should allow rough-and-tumble play when we can. Often on the playground, I would see guys (and girls) running, tackling, wrestling, and bouncing off one another. I usually keep an eye on it, making sure that the game is fun for everyone. Sometimes I need to intervene because it becomes less fun for someone. But, too often, I see other adults make kids stop that play. "Not appropriate" is what I hear. But, according to development, this type of play is important and allows kids to have that contact they need.

Physical contact is important for kids and for us adults, too.

Links from the book:

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)